Throughout its early history and before its expansion, the Monastery occupied a very small area. Built upon and restricted by the series of three consecutive, equal-sized, upright rocks almost independent from each other which protruded from the side of the mountain, the Monastery gradually developed. The early design scheme was depicted in the 1744 drawing of the Russian monk-traveller Vasileios Barski, but can still be seen today from the exterior of the north wing, opposite from the deep, sheer-sided ravine. The great tower of the Monastery stands upon the third rock towards the east, while a fourth rock of similar dimensions is found a little further eastwards, outside of the Monastery’s perimeter.

The first installation of monks took place at the end of the 10th century, when the monastery was referred to as Xeropotamos, or as the St Pavlos’ Monastery of the Most Holy Virgin Mary. It seems that the original structure was located at the middle rock, which is the site today of the chapel of St Georgios, built in the 16th century.

The present-day size of the area of the St Pavlos Monastery is the result of a very large expansion, the buildings of which were completed in gradual stages throughout the decades of the 19th century and into the first years of the 20th. Since then, the building complex of the Monastery has been limited approximately to the area occupied by the north side of the contemporary perimeter, from the northwest corner to the tower.

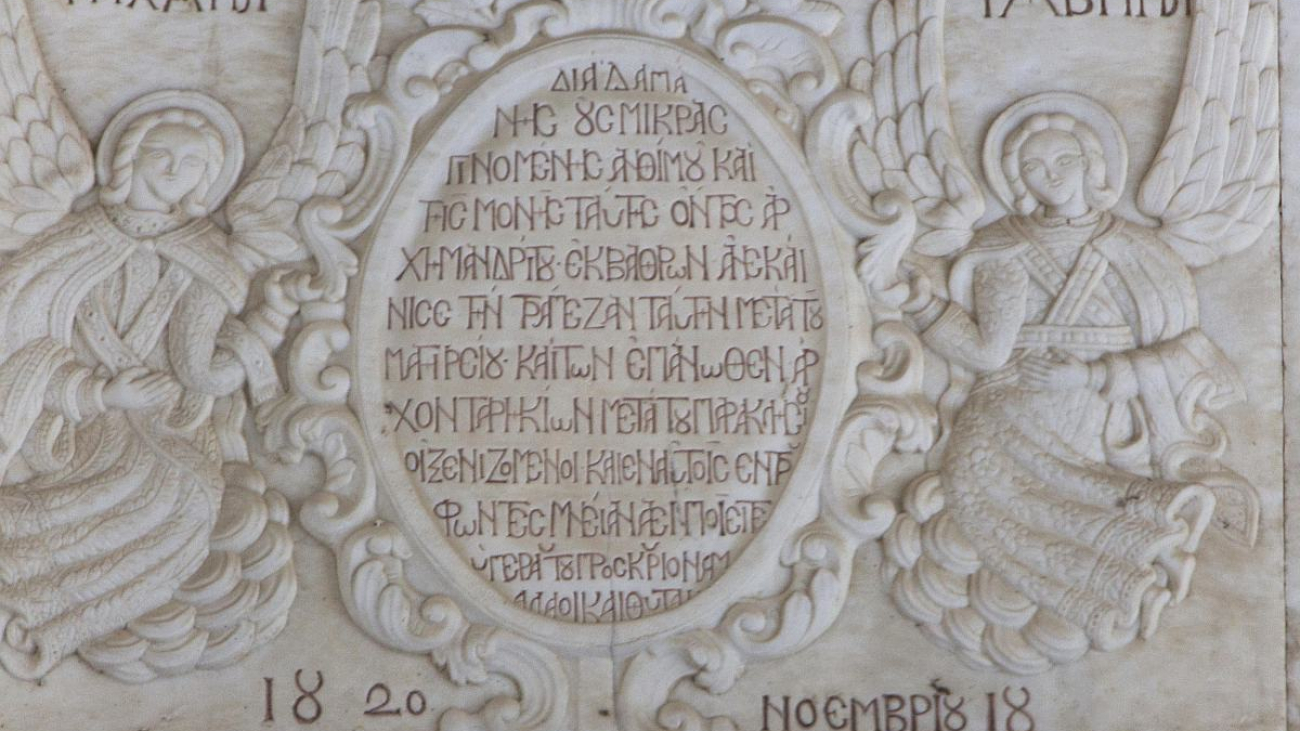

As mentioned previously, the expansion began in 1816 under the aegis of the Archimandrite Anthimos of the Monastery with the construction of the wall and the large west wing (including a new refectory and chapel), and the wooden frames of its upper-floor gallery. In 1819-1820, the present-day bell tower was constructed. During the last decade of the 19th century, extensive renovations and additions were made to the northwest section of the Monastery, from the central area where the chapel of St George is located to the edge of the north wing, up to and beyond the middle of the west wing. Finally, the west and the north wings were destroyed by fire in 1902, and later reconstructed into the form they have today. This work was designed and completed with an academic architectural approach influenced by the eclectic style of the time, as was also true for all the Athonite monasteries. This is very much observable in the most recent work completed during the first years of the 20th century, where the style of the structures surrounding the plaza at the entrance to the Monastery has been designed with an emblematic but restrained, simple and heavily classical look, especially observable in the tower above the entrance.

At the end of the first half of the 15th century, a (then) new cathedral was built at the Monastery, which was decorated with frescoes in 1446/7 and dedicated to the Virgin Mary and to St Georgios. The central nave of the church was located at the upper level of a three-storey building, which had been extended outward from the south side of the pre-existing complex, the entrance to which was remodelled and became the entrance to the Monastery. The three-storey building with its 15th century cathedral survived until about the middle of the 19th century, and is depicted in two very valuable copper engravings from 1744 and 1835, which are discussed in a previous section. Recent excavations by the Archaeological Service have uncovered the northeast corner of the building in the courtyard of the Monastery, northwest of the present-day cathedral.

The great tower of the Monastery was built in 1521/2 and was completed later, in the 16th century. It is likely that the small barbicon (i.e. fortified defensive structure; μπαρμπακάς) located at the front and west of the entrance to the tower must have been built immediately after the tower was constructed. These fortifications seem to have been complete in Barski’s 1744 drawing, but only the north wall and some remnants of the south wall have survived until today.

Upon the top of the rock, the small, two-storey building with the chapel of St Georgios must have been built during this same period, just prior to the middle of the 16th century, with the surviving remnants of earlier constructions being incorporated into it.

Finally, the contemporary building of the Sacristy, which was added in 2015 to the northeast section of the courtyard between the cathedral and the tower, is also worth noting.