The Library

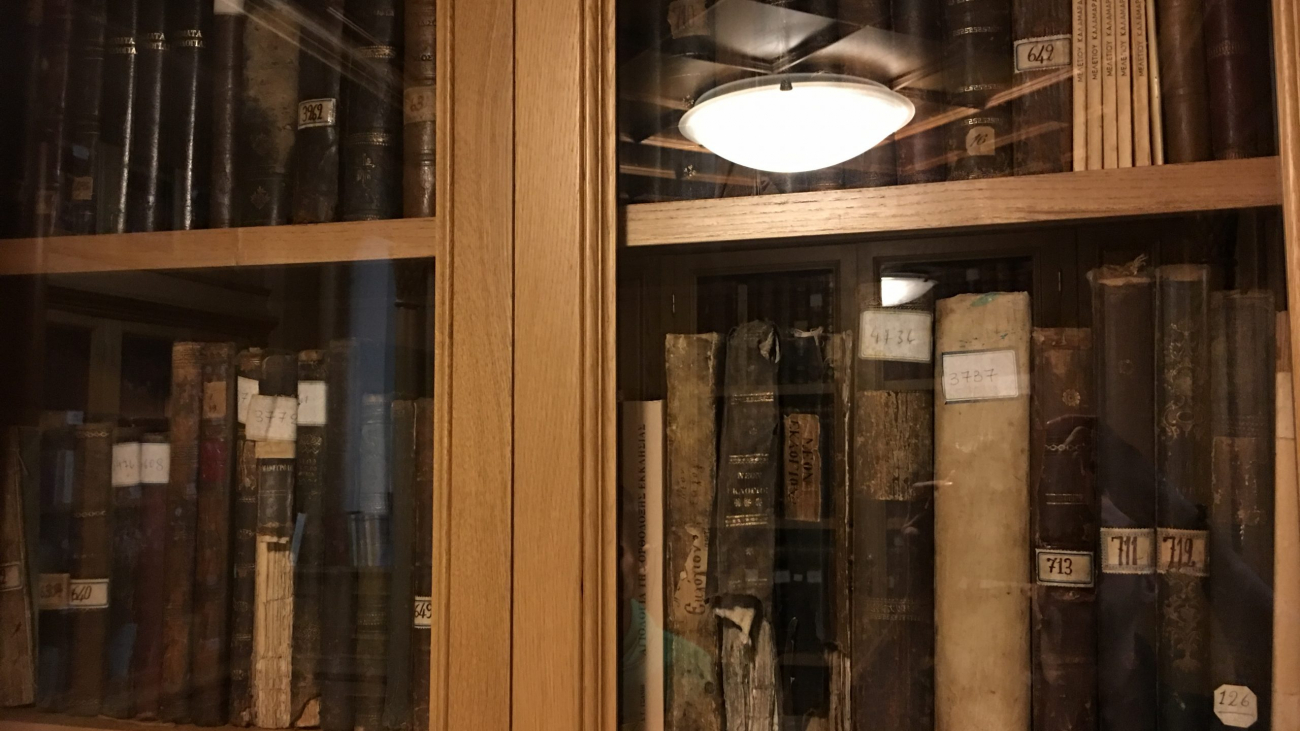

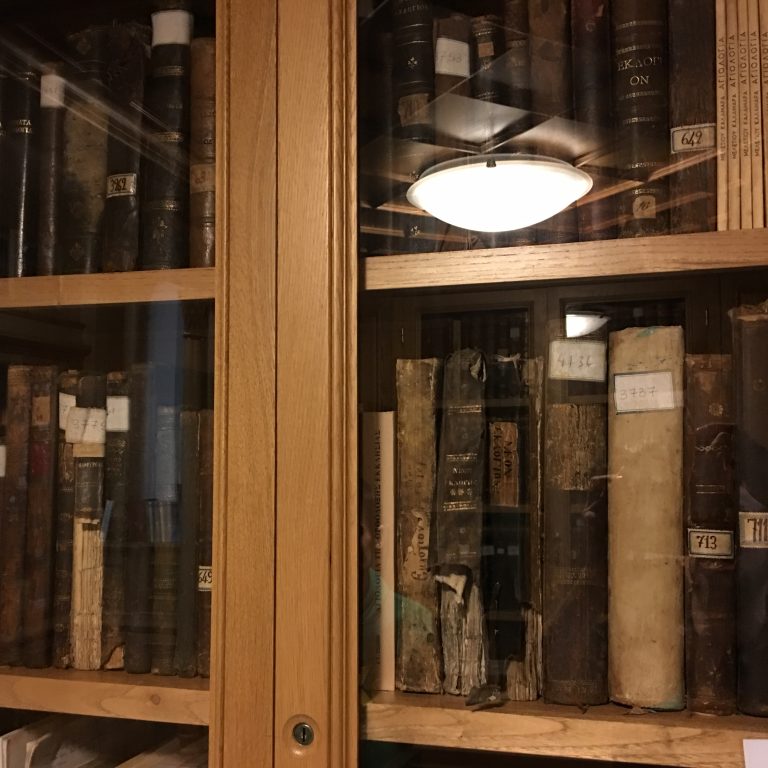

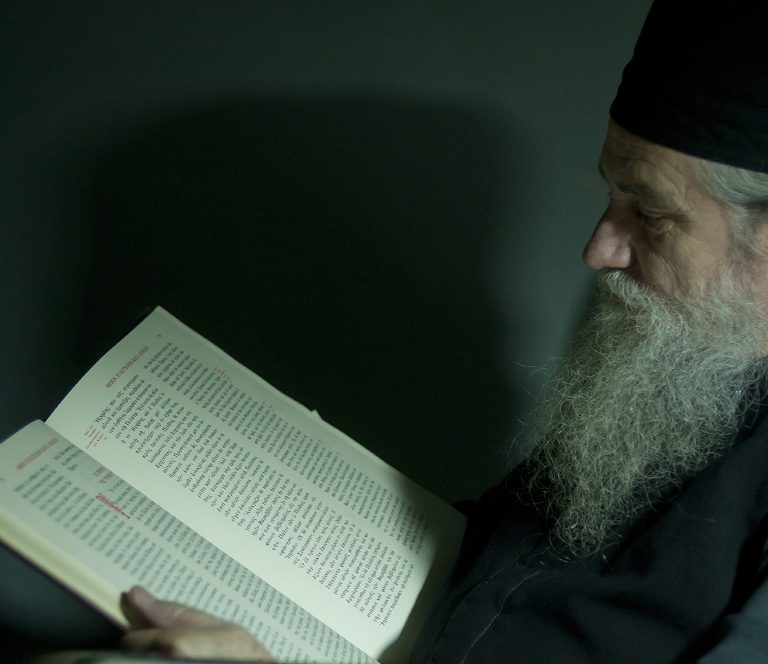

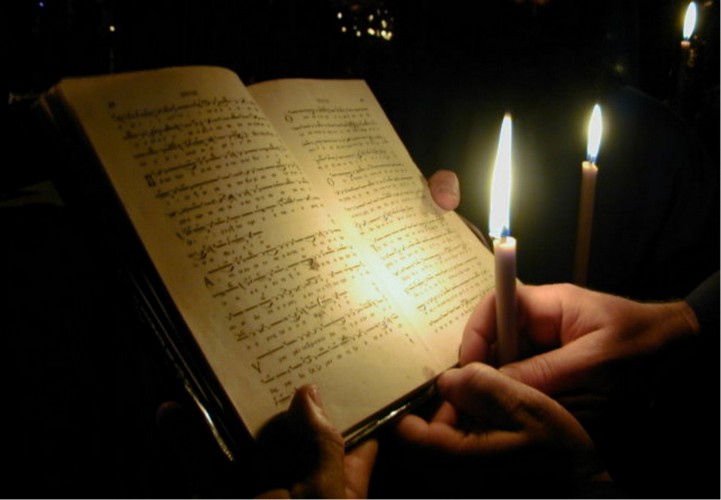

In the Middle Ages, books were precious, hard-to-find objects. An individual had access to books only if he were wealthy. The monks in a large monastery, in contrast, constantly had a complete library at their disposal, with works by the Church fathers, lives of the saints, and various works of both ancient and synchronous authors. The library of the Pantokratoros Monastery, which after its restoration is housed again on the second floor of the tower, contains 450 manuscripts and more than 3,500 printed books.

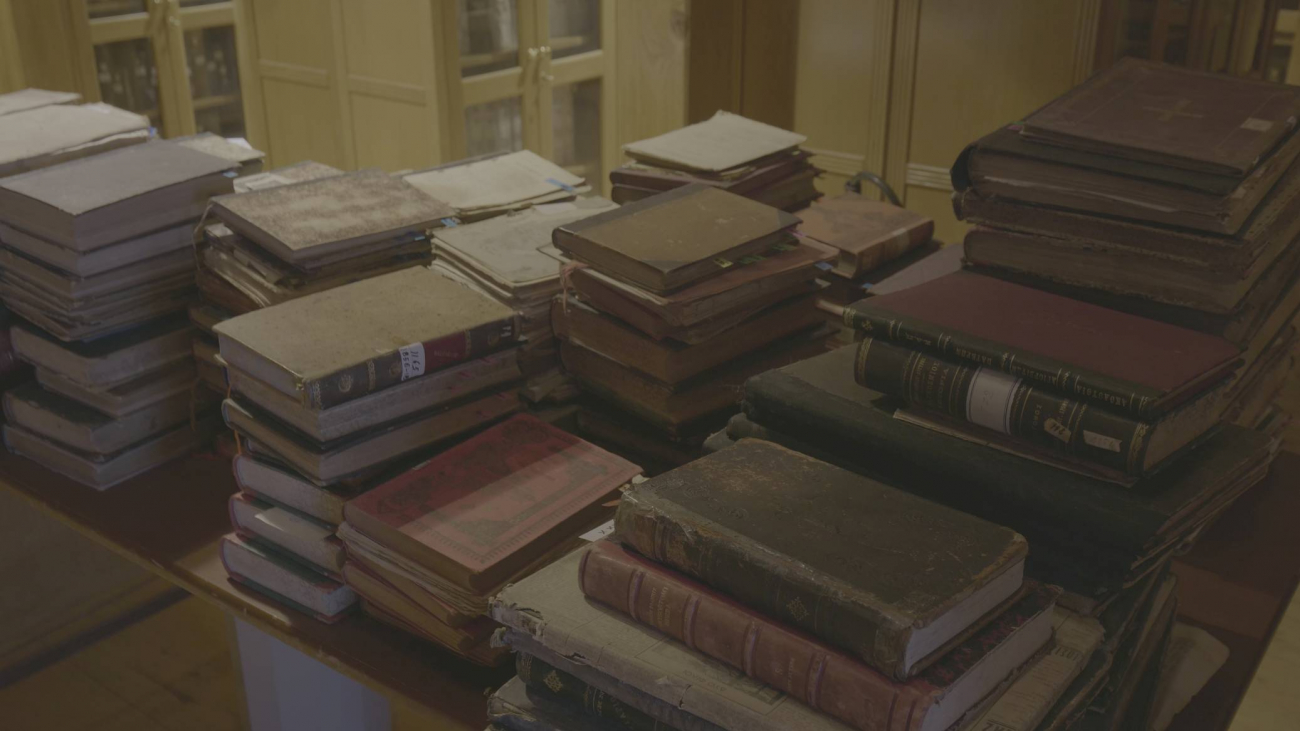

Over time, the library suffered serious losses and catastrophes, such as after the Revolution of 1821, but also through the seizure of many important manuscripts, some of which are found today in libraries abroad. A characteristic example is that involving Arsenios Souchanof who, while on a mission to Mt Athos in the 17th century for the Tsar and the Patriarch of Moscow, removed hundreds of books from the libraries of virtually all of the Athonite monasteries, including 31 manuscripts belonging to the Pantocratoros Monastery. These manuscripts can be found today in the collection of the Synodic Library of Moscow (now called the Historical Museum) numbered 30, 84, 90, 97, 106, 122, 130, 132, 135, 171, 176, 189, 191, 197, 207, 241, 280, 306, 307, 326, 341, 344, 348, 350, 354, 364, 369, 371, 410, 421, 464, in the catalogue of Vladimir, with the designation ‘Books of the Christos Pantokratoros [Monastery]’, or simply ‘from Pantokratoros’

Over time, the library suffered serious losses and catastrophes, such as after the Revolution of 1821, but also through the seizure of many important manuscripts, some of which are found today in libraries abroad. A characteristic example is that involving Arsenios Souchanof who, while on a mission to Mt Athos in the 17th century for the Tsar and the Patriarch of Moscow, removed hundreds of books from the libraries of virtually all of the Athonite monasteries, including 31 manuscripts belonging to the Pantocratoros Monastery. These manuscripts can be found today in the collection of the Synodic Library of Moscow (now called the Historical Museum) numbered 30, 84, 90, 97, 106, 122, 130, 132, 135, 171, 176, 189, 191, 197, 207, 241, 280, 306, 307, 326, 341, 344, 348, 350, 354, 364, 369, 371, 410, 421, 464, in the catalogue of Vladimir, with the designation ‘Books of the Christos Pantokratoros [Monastery]’, or simply ‘from Pantokratoros’