The Monastery During The Greek Revolution Of 1821

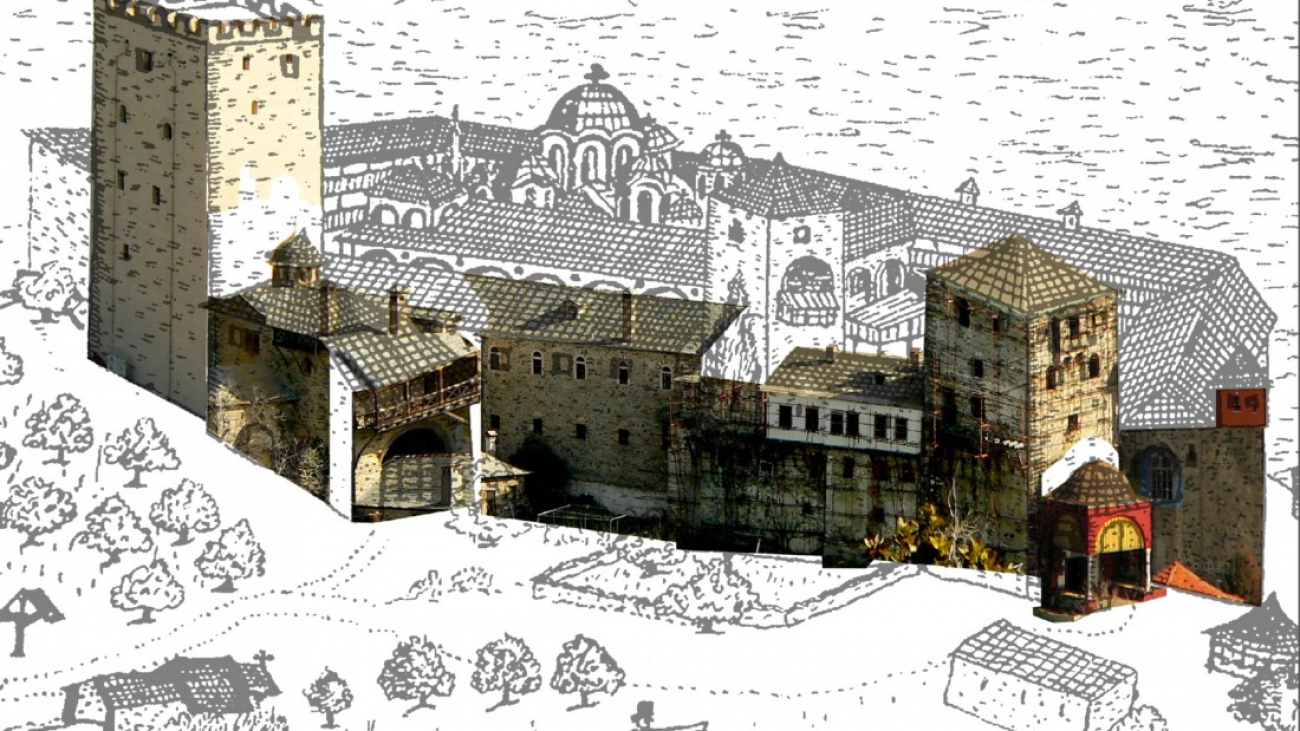

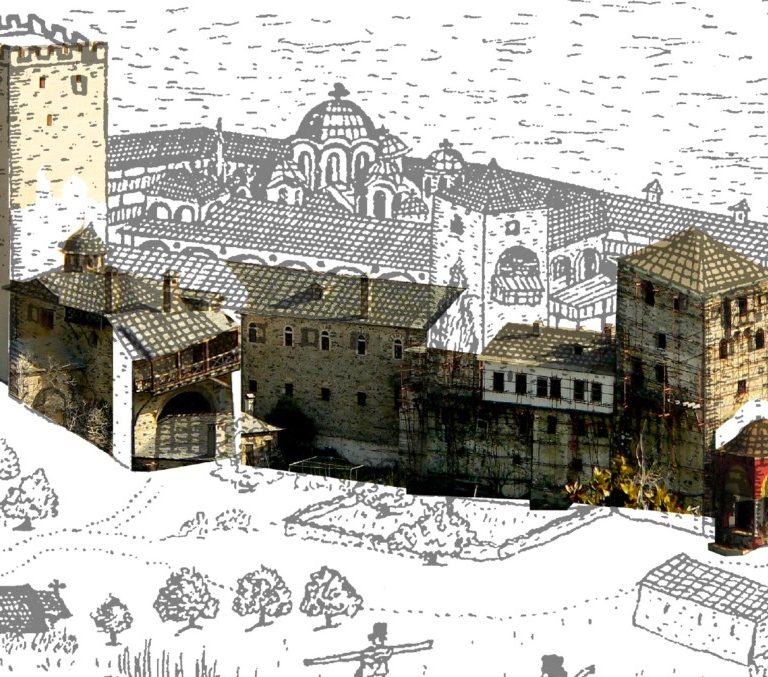

The Revolution of 1821 meant the start of great, new 'adventures' for the Monastery, and for the entire Agios Oros community. The Athonites publicly supported the revolutionary exploits of Immanuel Papa in eastern Macedonia. Moreover, according to oral tradition, the Monastery gave the cannons from its towers for use during the war, an event which is depicted in old engravings.

However, the failure of Papa's Macedonian forces created many problems for the Athonites. In February 1822, Turkish troops invaded and occupied the monasteries, forcing the monks to feed and house them. At the same time, heavy taxes were levied, driving the monasteries to absolute poverty. This is confirmed by comments in an 1827 report written by two officials of the Monastery, the Prior Theoclitos and the Elder Agapios: 'Now that it is known what has happened, we will be deprived of good bread.'

Most of the monks at the Monastery, as well as the other Athonite monks, had already abandoned Agios Oros before the invasion of the Turkish troops. They left on boats belonging to the Monastery, first sailing to Thasos and from there to Skopelos, carrying with them all the artifacts of the Monastery. Upon their arrival in Skopelos, the artifacts were recorded and given to Droso Mansolo and Kyriako Tasika, two high-ranking representatives of the Hellenic Parliament of Corinth, for the purpose of using them to help fill the needs of the revolution. The sacred liturgical vestments were protected at the Monastery of the Bishop in Skopelos.

According to K. Notara, the Minister of the Hellenic Economy at that time, the silver and gold obtained from the artefacts amounted to 6,250 Turkish coins ('grosia'), which does not reflect the true value of the items since it is does not take into account the historical value of the objects or the craftsmanship involved in their elaborate, artistic decoration. Any artefacts which were not used were taken to the Monastery of the Great Cave in the Peloponnese, from where they were eventually returned to the Monastery in 1830, after the withdrawal of the Turkish troops from Agios Oros, by order of the first Governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias.

After this long and difficult 'adventure' of its monks, the Monastery regrouped and reorganized. With grants from the Pantokratoros Archimandrite and Treasurer to its dependency in Blachia, Meletios Katsoranos of Kydonieos, significant renovations and repairs were made to buildings and particularly in the cathedral, where the frescoes were repainted. Despite the economic problems which continued to plague it, the Monastery experienced a gradual growth, and in 1903 had a population of 58 monks.

However, the failure of Papa's Macedonian forces created many problems for the Athonites. In February 1822, Turkish troops invaded and occupied the monasteries, forcing the monks to feed and house them. At the same time, heavy taxes were levied, driving the monasteries to absolute poverty. This is confirmed by comments in an 1827 report written by two officials of the Monastery, the Prior Theoclitos and the Elder Agapios: 'Now that it is known what has happened, we will be deprived of good bread.'

Most of the monks at the Monastery, as well as the other Athonite monks, had already abandoned Agios Oros before the invasion of the Turkish troops. They left on boats belonging to the Monastery, first sailing to Thasos and from there to Skopelos, carrying with them all the artifacts of the Monastery. Upon their arrival in Skopelos, the artifacts were recorded and given to Droso Mansolo and Kyriako Tasika, two high-ranking representatives of the Hellenic Parliament of Corinth, for the purpose of using them to help fill the needs of the revolution. The sacred liturgical vestments were protected at the Monastery of the Bishop in Skopelos.

According to K. Notara, the Minister of the Hellenic Economy at that time, the silver and gold obtained from the artefacts amounted to 6,250 Turkish coins ('grosia'), which does not reflect the true value of the items since it is does not take into account the historical value of the objects or the craftsmanship involved in their elaborate, artistic decoration. Any artefacts which were not used were taken to the Monastery of the Great Cave in the Peloponnese, from where they were eventually returned to the Monastery in 1830, after the withdrawal of the Turkish troops from Agios Oros, by order of the first Governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias.

After this long and difficult 'adventure' of its monks, the Monastery regrouped and reorganized. With grants from the Pantokratoros Archimandrite and Treasurer to its dependency in Blachia, Meletios Katsoranos of Kydonieos, significant renovations and repairs were made to buildings and particularly in the cathedral, where the frescoes were repainted. Despite the economic problems which continued to plague it, the Monastery experienced a gradual growth, and in 1903 had a population of 58 monks.